Ralph & James Clews

|

Ralph and James Clews, born in 1788 and 1790 respectively, were two of the sons of John Clews, a hatter, of Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire. We know little of their early life, but by 1811 James Clews was acting as clerk to the potter Andrew Stevenson,[1] and he and Ralph were in business on their own account by the autumn of 1813[2]. The Bleak Hill Works in Cobridge, near to Burslem was probably their first pottery. Bleak Hill, a small factory with two ovens, had been operated by Peter Warburton until his untimely death in January 1813 at the age of 40, and his widow Mary was advertising the works for sale or to let in the following month. An insurance policy which the widow Warburton took out in July 1817[3] specifies the premises as being in the occupation of Ralph and James Clews and it seems likely that the brothers took the opportunity presented by the empty factory when they first entered business in 1813. In 1817, the brothers rented a second factory in Cobridge, the Globe Works, and it was at this pottery they developed their enormous export trade to the United States. The Clews brothers continued to occupy the Bleak Hill factory until 1827, when the works was advertised to let and they took out a lease on the Cobridge Works of Andrew Stevenson[4]who had retired from business around that date[5]. The 1827 move from Bleak Hill to the much larger Cobridge Works was clearly intended to provide additional manufacturing capacity, the rent was double that of the nearby Globe Works which they continued to operate[6]. A major contribution to the growth of Clews’ business was their close relationship with the firm of merchants and importers Bolton, Ogden, & Co., who effectively financed the manufacturers by advancing a proportion of the value of consignments prior to sale. This arrangement resulted in Clews becoming substantially indebted to their importer. When production problems arose, due to industrial unrest in the Potteries in 1834, the business had no reserves to cope with the loss of revenue and the Clews brothers went bankrupt with enormous liabilities and relatively few assets. Bolton,Ogden & Co were owed over £68,000, of which some £35,000 was unsold ware. A number of contemporary references suggest that the Clews brothers were unscrupulous businessmen. They were known to be truck masters, that is, they paid some of their workforce in goods rather than money. Often the goods were substandard and could not be redeemed or bartered to produce even subsistence wages. The experience of James Sherratt, who worked for Ralph & James Clews, gives us an insight into the treatment of their workers. ‘James

Sherratt, of Hotlane in the Parish of Burslem, Potter, deposeth that he has

recently worked at the Manufactory of Messrs Job and John Jackson, of Burslem, who

have paid him for his labour in the most part in Goods; that for the last six

weeks he has not received any money, but has been paid entirely in Goods, which

have been charged considerably more than the retail prices of the Shopkeepers.... That before he worked for Messrs Jacksons,

he had been employed by Messrs. R. & J. Clews, of Cobridge, who also paid

him in goods. He has there had beef served out to him at 8d per lb, which he

could have purchased at 3d in the market, and other things proportionably dear.

That the beef was often ticketed; and on one occasion he had allotted to him 5

½ lb, of beef, out of which he separated and weighed 3 3/4lbs. of Bone. That Onions

have been forced on the men for payment, of which he received his share, but

they were of such a quality that he threw them away, being unfit for food.’ Matthew Smith, a Baltimore importer of Staffordshire wares, also had cause to complain of Clews business dealings. In November 1827, he sent his Liverpool agent particulars of a claim against Clews for crazed ware and dishes so crooked as to be unmerchantable: in May 1828 the agent reported that ‘they could not prevail on Clews to do what was right’.[8] Clews unashamedly plagiarised the popular patterns of other manufacturers being exported to America, employing an agent in the States to identify such patterns and send samples back to the factory where Clews workmen would re-engrave them.[9] Considerable records of Clews’ export trade survive in the papers of Ogden, Ferguson and Day[10], the American branch of their agents, which are in the collection of the New York Historical Society. These include invoices detailing the names of numerous patterns, of which relatively few are of American views or have a direct American interest; examples are the Landing of Lafayette and the Arms of the States[11]. Following their bankruptcy in 1834/35, James Clews moved to America. In 1836 he visited Louisville, Kentucky, where, unaware of his recent bankruptcy, the City offered him almost unlimited backing if he would set up a pottery to make fine earthenware nearby. Clews decided that suitable clay and coal were available at Troy Indiana a few miles down the Ohio River and the Indiana Pottery Co, was established[12]. In late 1836, Clews arranged the importation of thirty six potters, probably from the Staffordshire industry, which at that time was in the throes of a protracted strike. $50, 000 and two years later, a petition by the company to Congress dated 4th January 1838 stated that it was capable of producing ‘queensware and china’ but could not do so at a profit without access to the raw materials to be found on public lands. The petition was turned down; the pottery continued but James Clews sold his shares in 1842 and moved on. He sailed home with his wife and children in 1841 and sailed back and forth between Britain and North America over the next few years, perhaps finishing up business. By 1851 he is living with his family and servants at Ox Leasows, Stone , in Staffordshire where he died in 1861.[13]

[1] Wedgwood Manuscripts 33/25182 Courtesy Trustees of the Wedgwood Museum [2] Wedgwood Manuscripts 30/22 821-23 Courtesy Trustees of the Wedgwood Museum [3] Roger Edmundson, ‘Staffordshire Potters Insured with the Salop Fire Office 1780-182’ Northern Ceramic Society Journal Vol. 6, 1987, at p.92. [4] Later known as the Alexander Works [5] In the 1980s the Bleak Hill site was cleared for re-development and substantial quantities of shards relating to the Warburton and Clews periods were recovered. Analysis of these shards was able to establish that Clews earthenware production on the site encompassed both blue printed earthenware and underglaze polychrome painted tea wares. See Roger Pomfret ,‘The Bleak Hill Site’ Northern Ceramic Society Journal Vol 19 2002 pp.133-157. [6] Staffordshire Record Office papers D206/2 [7] Enoch Wood Scrapbook, Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire: [8] Roger Pomfret, ‘A Staffordshire Warehouse in Baltimore: The Letter Books of Matthew Smith 1806-32’, Northern Ceramic Society Journal Vol.26 2010 pp.100 & 102. [9] George L. Miller., Ann Smart Martin and Nancy S. Dickinson (1994) “Changing Consumption Patterns: English Ceramics and the American Market from 1770 to 1840”, Everyday Life in the Early Republic, Catherine E. Hutchins, editor, pp. 219-248. Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware. [10] Collection of the New York Historical Society. [11] No pattern is known marked with this name, it is probably the pattern that collectors call “American & Independence” [12] J. Garrison Stradling, “Ceramics”. The encyclopedia of Louisville. ed. John E Kleber 2001Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. [13] 1851 British Census and Frank Stefano Jnr,, ‘James Clews, 19th Century Potter, Part II,” The Magazine Antiques, March 1974 pp.553-555 |

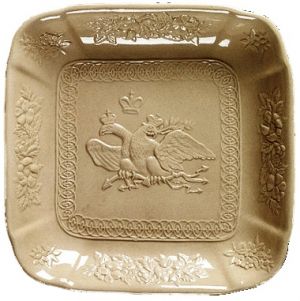

Pearlware plate underglaze painted decoration. R. & J. ClewsWinterthur Museum  Pearlware plate Pearlware plate printed with portrait of LaFayette R. & J. ClewsWintethur Museum  Black print entitled "Picturesque Views, Black print entitled "Picturesque Views, Nr. Fishkill, Hudson River"R. & J. ClewsWinterthur Museum  Earthenware dish Earthenware dish moulded with a Russian eagleR. & J. Clews©Victoria and Albert Museum, London  Pearlware plate Pearlware plate molded and undeglaze painted decoration.R. & J. ClewsWinterthur Museum |